There has been a lot of hype around the use of transfer learning for image classification tasks and with good reason. Transfer learning is an easy way to get state-of-the-art results on many image classification tasks without much headache. The problem with this is that it can lead to many “black box” results where the models aren’t fully understood by the people implementing them. In order to try and better understand some of these more advanced CNN architectures I decided to build a custom CNN image classifier from the ground up.

The Task:

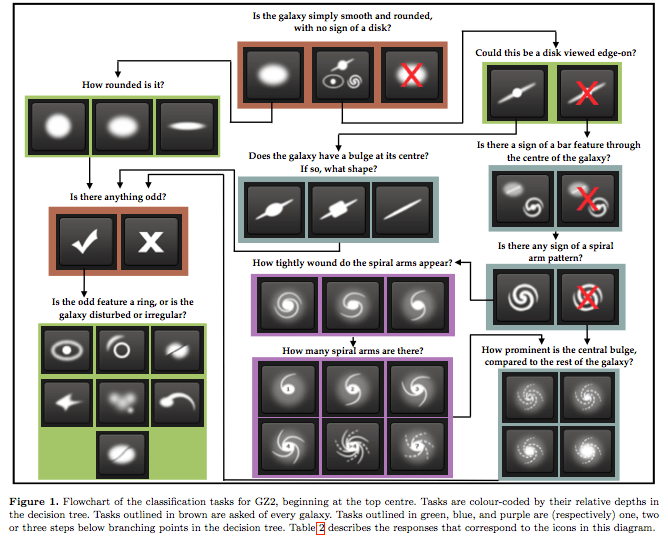

The task I decided to take on was the Galaxy Zoo challenge hosted on Kaggle. Galaxy zoo is one of the largest crowdsourced surveys ever done. It polled people to identify different types of galaxy shapes through the use of a simple survey:

Despite the enormous success of galaxy zoo, the structure for attaining reliable labels for these images becomes less feasible as the number of images moves from hundreds of thousands to hundreds of millions. An image classifier is therefore useful to leverage these existing labels in order to predict future ones.

The Model:

The biggest hindrance to overcome when building this model was that I wanted to do all of my training on my laptop. In order for that to feasible I had to create a network with a relatively low number of parameters and reduce the dimensionality of my images.

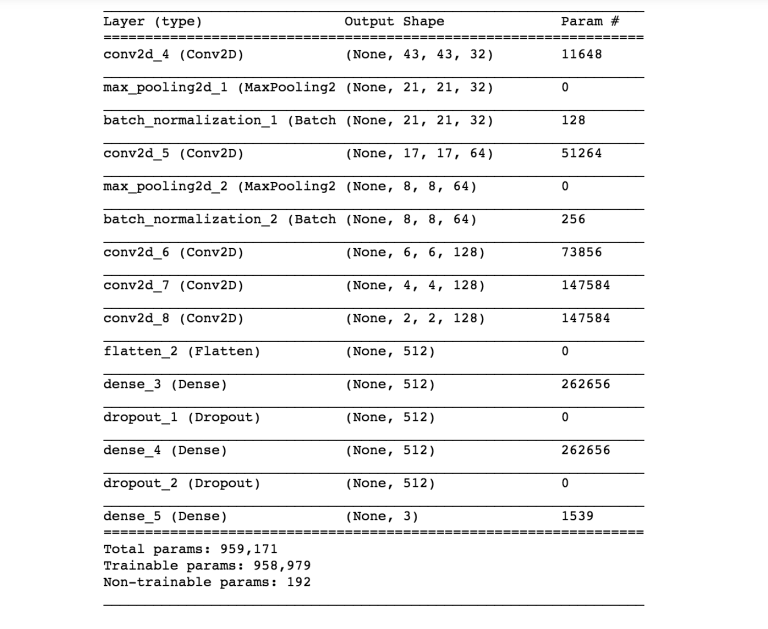

Over the course of this project I tried hundreds of architectures and quickly found that trial and error wasn’t going to get me anywhere. The model ended up being based on the architecture of AlexNet. It consisted of 5 convolutional layers, 2 pooling layers, and 3 dense layers (code available on my github).

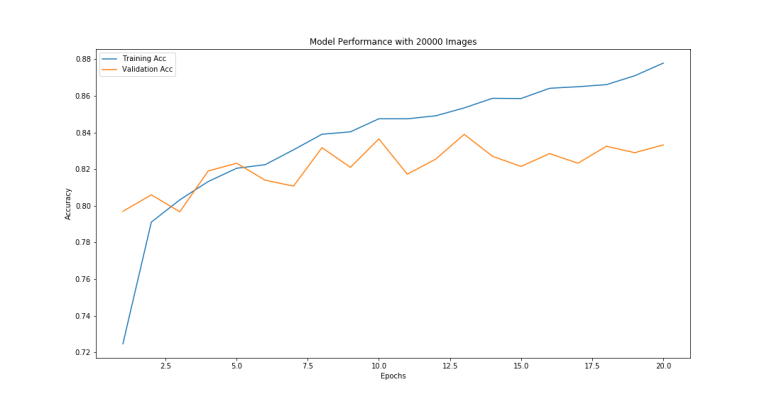

The model utilizes subsampling in the first three convolutional layers which is what allows training to be feasible on a conventional laptop (more on this later). Ultimately the model was able to identify the correct answer of the first survey question (smooth, features, or disk) with ~84% accuracy.

What I Learned:

1) Every value is important:

Its easy to take these incredibly complex models like ResNet and Xception for granted when we are using them. Without prior knowledge each parameter may as well seem random, but each one has been specifically chosen and impacts the performance of the model. Trying random layer sizes and depths isn’t going to get you anywhere fast so it’s imperative that you understand what your model is actually doing at each layer in order to start building layers through intuition rather than random guessing.

2) Even “simple” architectures will overfit if not kept in check.

CNNs really are amazing. Even shallow networks can overfit quite quickly if you are not adding regularization techniques. For this task the best ways to deal with overfitting was adding more data and to add regularization methods such as dropout layers. You can use your understanding of the task to add appropriate data augmentation and further improve your model by giving it more samples to train on. Just make sure that the augmentation is actually going to preserve the label. For example rotation was appropriate for this task but won’t be for all others.

3) Deeper isn’t better:

I may be beating a dead horse here, but you can’t make your model better by mindlessly stacking more layers. In order to gain better results you need to understand the dimensionality of your features at each layer and keep track of things like your models local receptive field.

The local receptive field is a concept specific to CNNs. Unlike Densely connected layers, each unit in a convolutional layer depends only on a certain region of the initial input. This region of the input is called the receptive field for that unit [1].

Stacking convolutional layers will increase the receptive field linearly while sub-sampling will increase it multiplicatively [1]. By the end of your convolutional network you want the receptive field to be large enough for it to make reasonable predictions for the entire image. For this problem simply stacking convolutional layers resulted in too many parameters for training to be feasible on a laptop. Therefore in order to reduce the number of parameters (and therefor train time), subsampling needed to be utilized. This allowed the receptive field of the final convolutional layers to be large and training time reasonably low. Utilizing subsampling on the first few layers has some obvious drawbacks. Because this model subsamples so aggressively it cannot pick up on some smaller scale features that might otherwise have helped it to correctly classify images.

Keeping track of things like this will not only allow you to build better networks but will allow you to understand why they are better.

4) Don’t try and train an image classifier on your laptop.

Perhaps this goes without saying, but I will go on record here and say its not a good idea. Though this project allowed me to understand a lot about reducing dimensionality and how to gear a network towards lower computation it’s really not something you should be doing. If you are serious about creating an image classifier you are going to need a GPU to train your models. Cloud computing is a great resource which can allow you to train modern networks on GPUs and has been my approach to all future image classification tasks I have done since this one.

Takeaways:

Transfer learning is popular for a reason. Unless you’re doing serious deep learning research it’s unlikely you will beat the results you would see from transfer learning with a custom network. That being said transfer learning can be somewhat limited and understanding the impact of each layer will give you a much more insight when trying to improve any network you work on. Additionally custom networks can give you much more flexibility for your tasks when faced with certain factors such as low computational resources.

Sources:

[1] Understanding the Effective Receptive Field in Deep Convolutional Neural Networks, Wenjie Luo, Yujia Li, Raquel Urtasun, Richard Zemel, University of Toronto, from http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~wenjie/papers/nips16/top.pdfhttp://www.cs.toronto.edu/~wenjie/papers/nips16/top.pdf